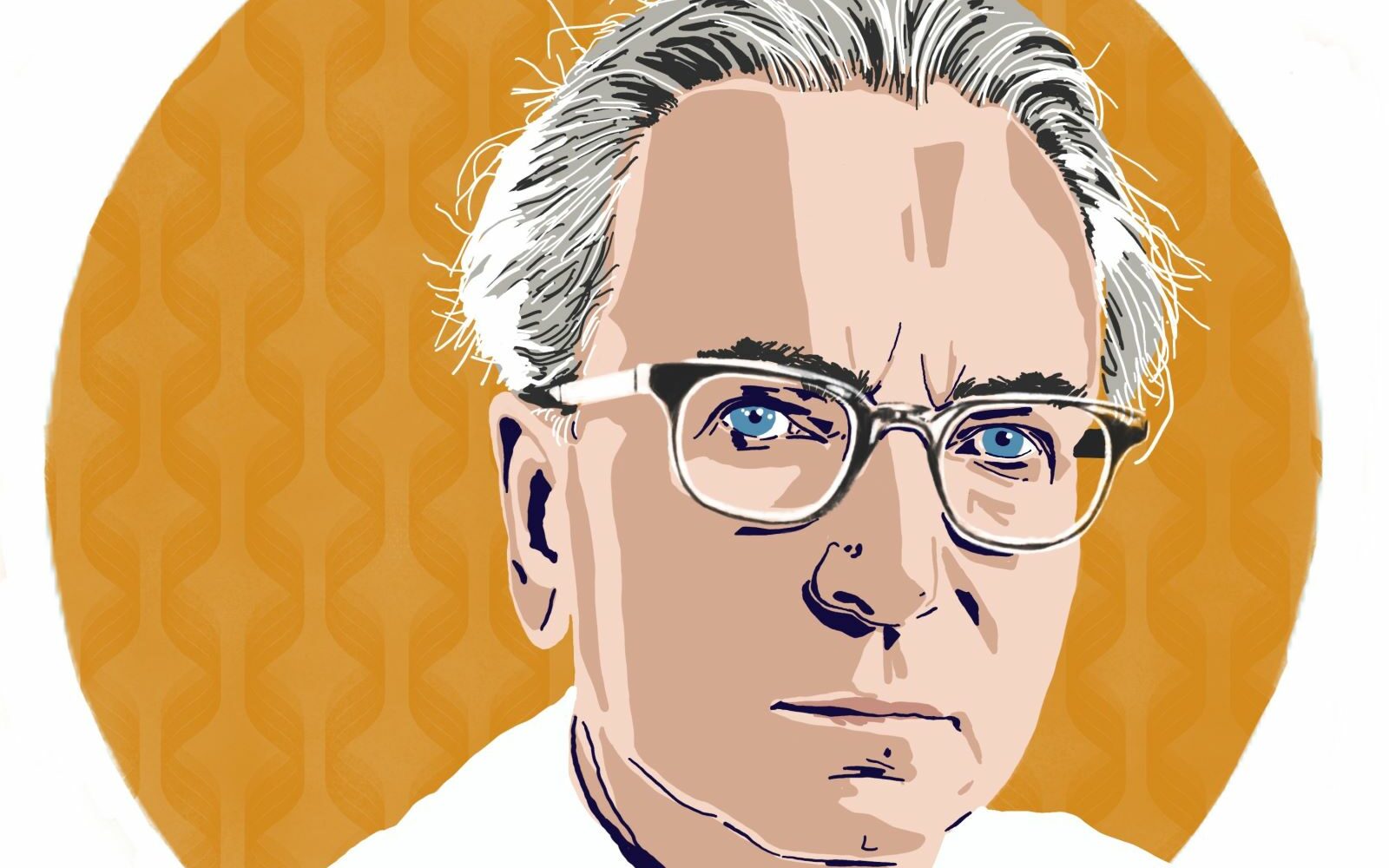

How Begin and Brzezinski built a relationship that led to the Camp David Accords

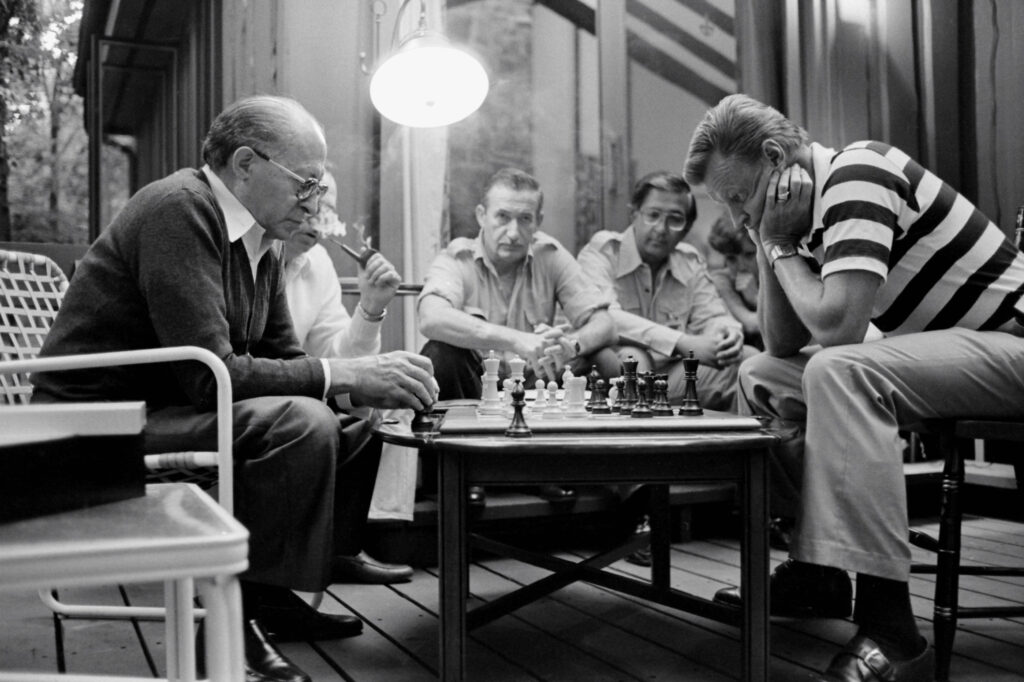

Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin quickly realized that his first meetings with Zbigniew Brzezinski, Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor, were not going well. These meetings took place in July of 1977 when Israel was in the middle of a crisis with both Egypt and Syria, making it a particularly precarious time for the United States/Israeli relationship to be transitioning to both a new President and a new Prime Minister.

Begin and Brzezinski had a complicated history. Both men were born in Poland but had vastly different Polish upbringings. Begin had been subjected to torture as a result of his heritage, while Brzezinski’s father was a distinguished Polish diplomat. Standing between these two leaders was the possibility that Begin could be associating Brzezinski with the atrocities that he had experienced earlier in his life.

A pretty dramatic day at the office, wouldn’t you say?

World peace may not hinge on the results of our meetings and there isn’t the same history of cross team friction that would equate to what Begin and Brzezinski faced that day, but on our much simpler level this story can be relatable. The meetings we have during our workday impact the business we’re a part of, which then has a much larger impact on people and their livelihoods. We care about the outcome and feel a responsibility to make the best choices possible to enable that business growth. We can acknowledge that while most workplace friction can be quickly ironed out, there are times when more complicated issues arise. For example, the feeling of cross team collaboration when there had recently been a project that failed to meet a deadline, impacting important sales goals and bonuses. For a meeting to be purposeful, there’s a base requirement of mutual respect and trust. In its own way, this story is a vastly dramatized version of what some meetings look like.

What Begin did next is a masterclass in leadership. He realized that he needed to settle the ghosts of the past before he and Brzezinski could form an emotional connection to work together. Begin invited Brzezinski for an unscheduled breakfast meeting at Blair House. To Brzezinski’s credit he agreed to the meeting, assuming it would be an opportunity for an off the record discussion. When Brzezinski’s car pulled up to Blair House he was surprised to see a bank of TV cameras and reporters lined up. Begin came forward. He greeted Brzezinski with a tremendous smile and warmly ushered Brzezinski forward. In front of the entire assembled media, he made it clear that he accepted Brzezinski. Begin then went further in showing that not only did he accept Brzezinski, but that Brzezinski had nothing to even consider needed forgiving between the two men. This last piece, the real work of showing that nothing needed forgiveness, was the critical step that Begin took.

Begin had understood that one could not just shake hands and claim bygones are bygones for what was the root of the friction here. To address that core problem, Begin dug deep into the Holocaust archives and unearthed a dossier that showed that Brzezinski’s father had helped the efforts to rescue European Jews from Nazi concentration camps. This proof dispelled any notion that Begin may have been aligning Brzezinski’s character with any of the inhumane experiences from Begin’s past. As one could imagine, Brzezinski was quite emotional to hear this public high praise of his father. He also shared with Begin that the timing, when he was being harshly attacked as anti-Israel, touched him deeply.

Begin’s gesture was genuine. He understood the burden that Brzezinski carried. He understood that for the two to work together, Brzezinski had to know he was respected. By all accounts, Brzezinski was an academically brilliant man. This gesture wasn’t a bribe or a trick designed to give Brzezinski a little ego boost with the hope that he would now have Brzezinski’s vote. Brzezinski was much too sophisticated for Begin to have thought that. What Begin did was send a clear message that they were two dignified men, aligned on the important matters of humanity and to use this base as a way forward. As history has shown, these first meetings were the foundation for the famous Camp David Accords.

Also Read: Ready for In-Person meetings? Dress for Success with Sustainable Fashion.

Let’s go back to our earlier challenges where a team sees the onus of a missed deadline belonging to another team. The easy way to address that conflict would be for someone to pull out their best Hank Stram motivational speech, remind everyone that we all make mistakes and that we’ll do better next time. Smile, shake hands and let bygones be bygones. Does that work? It might work, but more likely than not it just made those colleagues feel invalidated and has them withdraw further.

We know that our memories are more vivid and hardwired when there is trauma or disruption associated with a memory. Projects going well follow the expected path; projects missing their designed objectives create more disruption and chaos, which is the memory we carry. When we think about a person or an event, our mental retrieval process is biased towards retrieving what’s most imprinted in our memory. That negative occurrence is sitting front and center and pushing the good experiences further back. These colleagues are walking into their meetings without feeling that key baseline support; that they’re trusted and respected to help shepherd this new project to a successful outcome. They assume that their most recent performance is the lens through which they are being viewed.

Also Read: The Importance of Meditating Before, During and After Meetings

Before turning to the go-to team building exercises, there are five foundational steps to properly empathize with your colleague:

- Recognize that the history of past projects are finding their way into this new project.

- Recognize that to these colleagues the judgement they feel is very real and creating extra noise in their head.

- Put in the work to see if you can address the underlying friction. Clearing the air is the final step, not the first. The first step is to see if you can disassociate the results from the last project from the character of the people involved. This takes careful thought, especially when those colleagues can’t be completely absolved of responsibility. Keep in mind that rarely is a person the single factor in a project missing an objective. For example, if the deadline was missed because the work from home structure caused too much distraction, there’s an external factor to look at. We know that finding childcare is a universal struggle these days. Point to the problem, not the people. Doing so can help soften the messaging and suggest a character disassociation.

- Look for ways to fix the problem. For example, create a Slack channel for people to share their solutions for last minute childcare needs. Suggest to HR a benefits program that offers people a certain number of babysitting hours per month. There are so many creative solutions that can help a great teammate know that you have that baseline of respect for who they are and what they’re experiencing.

- Re-frame the memories being retrieved by addressing specific details of the successful projects. This helps reprogram our availability bias. You may need to do some research to find the right stories, but the time investment upfront will no doubt contribute to a smoother, respectful path forward.

References